Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (1993)

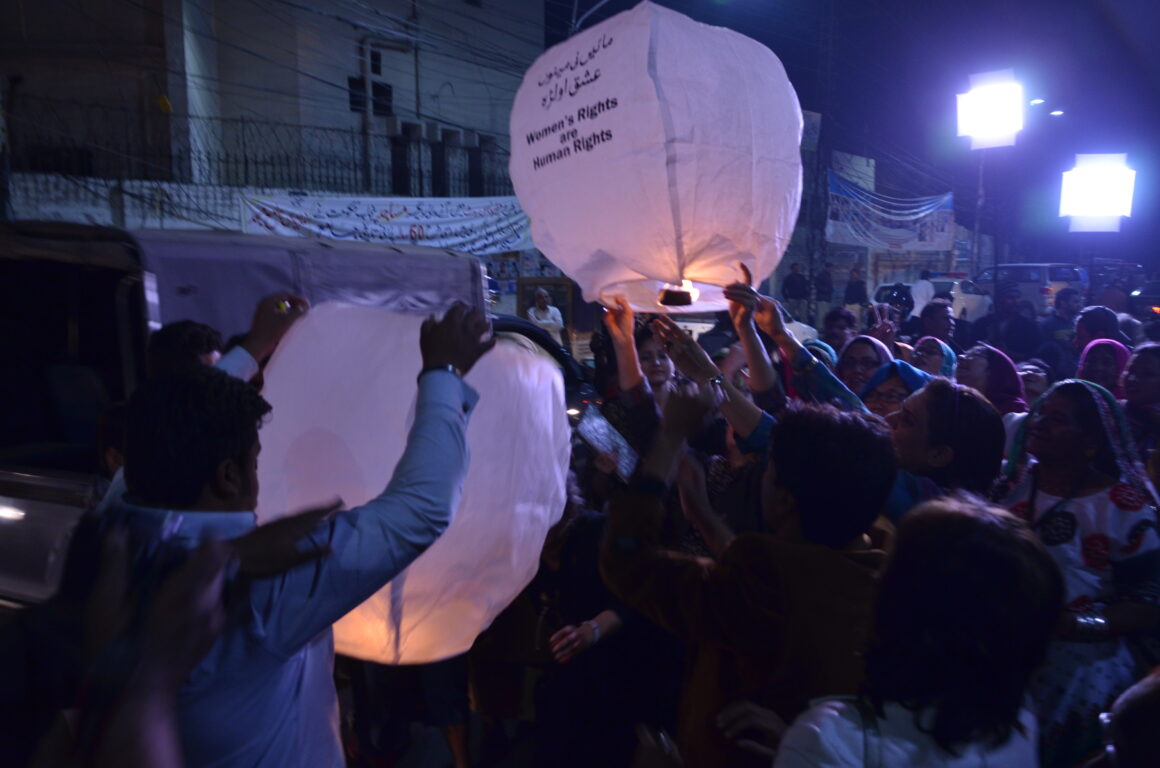

Women’s Rights Are Human Rights (1988 -1993)

Women’s Role in Peacebuilding (1995-2000)

Rape as a Weapon of War (1990s-2008 )

Maintenance

History of WLUML begun with Marieme Helie-Locus campaigned to release Algerian women, jailed for the opposition to the introduction of ‘Islamic’ Family Law in 1982. Subsequently, she at the request of Indian feminists organizations mobilized in support of the now-famous Shah Bano Begum maintenance case which is now viewed as milestones in Muslim women’s struggle for rights and justice in India. The mobilization around this case in Muslim majority countries also lead to further discussion on women’s rights within what was Muslim family laws. A third campaign was for the release of a Sri Lankan domestic worker in Abu Dhabi who was raped by her employer and because she had no witnesses to support her rape case, her pregnancy was treated as evidence of adultery and she was sentenced to death by stoning after the birth of her child. Marieme actively joined the campaign for her release and mobilized women and men in support of her case and she was released. Upon these successful interventions, She invited women to form the Muslim majority countries to form a solidarity network in support of women’s struggle for equality in the Muslim context and globally. Thus Campaign has been at the heart and a major pillar of Women Living Under Muslim Laws (WLUML) since its inception in 1984. WLUML has been part of the global advocacy movement for the recognition of Women’s Rights as Human Rights and advocacy for the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (DEVAW), along with women and peace-building from its inception.

Activism to Stop Violence Against Women (VAW) whether it was legal, cultural, or that it was justified based on religion or whether it took place in public or domestic spaces had been at the heart of WLUML research and advocacy and indeed it has been its raison de’etre since its inception in 1984. Thus, collaboration with transnational women’s movements has been built in its goals and priorities. WLUML joined the Transnational Working Groups who were focusing on eradicate violence against women through creating public awareness on discrimination and violence against women with an eye to create international instruments that can support the locally and nationally based movements to address these concerns.

The question of Gender-Based Violence (GBV) has been the focus of the international women’s movement from as far back as the early 19th century. However, since the 1975 UN conference on Women and Development and the decade of women and development, the transnational women’s movement has entered a new phase. The transnational women’s movement designated November 25 as a day against gender-based violence and formed several consortium working groups which work on specific dimensions of women’s concerns, including reproductive rights, women’s participation in politics, the eradication of VAW, and the recognition of women’s rights as human rights.

Indeed, since 1991, WLUML and the international working group – a consortium of various women’s organizations – joined the 16 Days of Activism which was launched by The Center for Women’s Global Leadership, and which has now evolved as an annual campaigning event. Each year the campaign may have a different theme based on what its networkers deem as an important concern of women in the diverse contexts that WLUML is active and has a presence. Local campaigns that would take place globally were part of the sustained transactional activism, lobbying and research in support of the various demands of the transnational women’s movement starting with the recognition that women’s rights are human rights.

June 15, 1993

The Global Tribunal on Violations of Women’s Human Rights at the United Nations World Conference on Human Rights (Vienna)

The Global Tribunal on Violations of Women’s Human Rights was a key feature of the Global Campaign for Women’s Human Rights and of the many NGO activities organized at the Vienna Conference by women’s groups. In addition to getting large numbers of women to Vienna, members of the Global Campaign provided a background paper and led a working group of over 200 women at the NGO event immediately prior to the UN Human Rights Council, demanding that women’s rights formally be recognized as human rights. This campaign led to a belated recognition of women’s human rights, giving women a formal, internationally recognized instrument in order to address the various inequalities that they faced in terms of economic, political, and social opportunities.

This meeting before the time of the internet and social media provided an opportunity for many women advocates and NGOs to meet and exchange ideas for furthering women’s rights and gender equality. Activists and NGO representatives mingled and exchanged information at the forum, called “A Woman’s Place” where information on the many women’s events and opportunities to collectively strategize were provided.

As a part of this campaign held on June 15, a Tribunal was organized by the Center for Women’s Global Leadership (CWGL)under the leadership of Charlotte Bunch and in collaboration with a number of other organizations. In a day-long event, 33 women from 25 countries presented testimonies on VAW, violations of women’s human rights in the family, at war, as well as societal, legal and economic violence and discrimination against women’s bodies and minds. Testimonies sought to concretely show how violations of human rights principles occurred in women’s daily lives and to contribute to documenting, defining, and making visible violations which had previously been inadequately addressed. The Global Tribunal in Vienna was the first of five international tribunals organized by CWGL to push the issue of women’s rights onto the global agenda. (CWGL made a documentary, The Vienna Tribunal, that includes highlights of the moving personal testimonies at the tribunal).

The years of activism and advocacy led the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna (1993) to recognize women’s rights as human rights; Vienna Declaration and in December 1993 the UN General Assembly’s adopted Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (DEVAW). One of the goals for the adoption of the resolution was to change the prevailing governments’ perspective that VAW was a private/domestic, cultural matter that did not necessitate state intervention. Indeed, CEDAW did not have a direct clause on Violence against women (VAW), and DEVAW had meant to address this shortcoming.

What gave this instrument a little more support of the local demands was that on 4 March 1994, the Human Rights Council passed Resolution 1994/45 on the question of integrating the rights of women into the human rights mechanisms of the UN and the elimination of violence against women. This Resolution established the mandate of the “Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women, and its causes and consequences”. The initial appointment was for a 3-year period. The rapporteurs are nominated by civil society. This instrument has brought about considerable public recognition of the various forms of violence that women face in many societies, with some states moving to introduce more women-friendly legislation to address these concerns.

At this stage, the focus was directed to address the reproductive rights of women and control over their bodies since the Cairo conference 1994 on the Population and Development (ICPD). The working groups managed to influence the policy document of these meetings and take the focus from women’s wombs to the women as individuals and as citizens.

The following year was the Beijing Women and Development Conference; an estimated 36,000 women from all over the world and from all walks of life attended. This large women’s conference culminated in the creation of the document Beijing Planform of Action that was to guide national and international policies for the next decades. It did influence international policies and development funds and created an instrument to women’s advocate for practical avenues to improve the life options of women. The 1995 Beijing Platform for Action contained an entire chapter focused on women, peace, and security. During the 1990s, the NGO community was increasingly concerned about the negative impacts of war and militarization policies on women. These concerns were heightened given the widespread sexual violence committed in civil wars in Bosnia, West Africa, and Rwanda. Activists were also troubled that women faced significant barriers to participating in peace talks and thus their experiences and negative impacts that women experienced during and post-conflict remained marginal to the talks. Yet in, Rwanda and Bosnia, where women suffered most, they were also the ones that took a leadership role in rebuilding their community. Transnational NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security (NGO WG) lobbied with the UN and several decision-makers, documenting what had happened on the ground and within communities where women had begun to rebuild their war-torn societies.

The Beijing Conference’s 5th anniversary (Beijing+5) provided critical momentum for progress on women, peace, and security issues at the UN. The working group had secured the support of several key women in the UN councils and had the support of UNIFEM and UNICEF. During these meetings, the Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah, then Minister of Women’s Affairs in Namibia, initiated the resolution when the country took its turn chairing the Security Council. Ambassador Anwarul Chowdhury, representing Bangladesh at the Council, also made significant contributions by using Bangladesh’s role as Council President to bring attention to women’s contributions to peace and security. The resolution was passed unanimously in October 2000.

The history of the NGO Working Group indicates that they played a critical in successfully lobbying the Council to hold open sessions on women, peace, and security. This allowed them to consult, lobby, and provide Council members with applicable information, paving the way for this historic resolution to pass

Following this success, a more concerted effort was directed on the recognition of rape as a weapon of war. This demand faced much more resistance by the various states including many of the NATO alliance countries and the USA and Japan in particular. However, resolution 1820 (https://www.peacewomen.org/SCR-1820 ) on Women and Rape was finally passed by the UN in 2008.